A new technique for preserving functional body tissues, even after they die, could help make more organs available for transplant.

Pigs used as guinea pigs were dead for one hour. Cause: cardiac arrest. However, six hours after researchers at Yale University connected their bodies to a machine that fed them a nutrient-rich components liquid, their organs began to show signs of life again.

Although the organs did not suddenly begin to function normally, some of the cellular damage caused by the loss of blood flow bloodafter their deaths, they seemed to reverse. The pigs' hearts emitted electrical activity. The cells in their kidneys, liver and lungs were working again and showing signs of repair.

The discovery, which published Wednesday in the journal Nature, suggests that cell death could be delayed longer than previously thought. If these processes could be slowed down even further, it could mean saving more organs for transplant.

"This new system has shown that not only can we slow cell damage, but that we can actually activate processes at the genetic level for cell repair," says Brendan Parent, assistant professor of bioethics at New York University, who was not involved. in the study, but contributed a commentary to Nature along with the study. "This may force us to rethink the way we decide something is 'dead'."

In 2019, the same Yale team challenged the idea that brain death is definitive when they reported that they had partially revived pig brains for hours after the animals were slaughtered. For the current experiment, the researchers wanted to see if the same method, in which a blood substitute is delivered to the animal's circulatory system, could also be used to revive other organs.

"We restored certain cell functions in multiple vital organs that would have died without our interventions," added lead author Nenad Sestan, a Yale neuroscientist. "These cells are functioning hours after they were 'dead' and what this tells us is that cell death can be stopped and the functionaltheir ability to be restored to many vital organs, even an hour after death.'

The standard practice for preserving organs for transplantation is static storage in a refrigerator. Rapid cooling of organs after removal reduces oxygen demand and can prevent cell death, but does not save every organ.

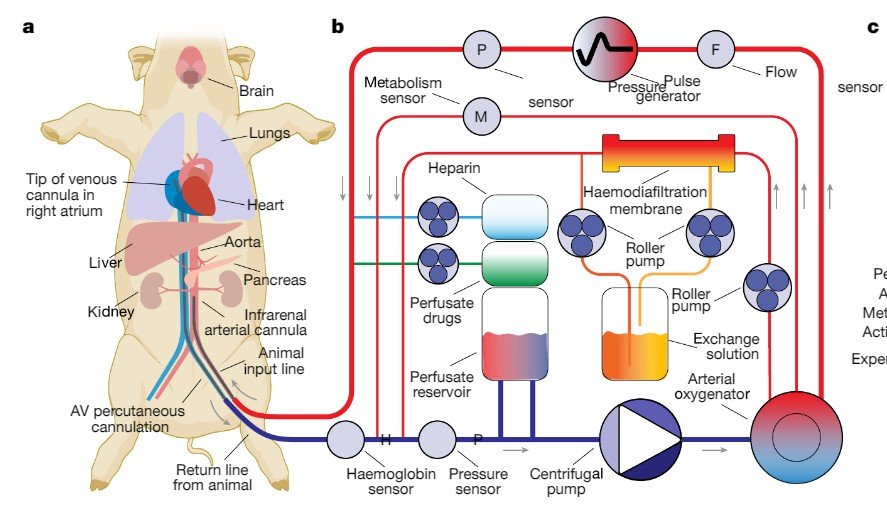

Yale's technique, called OrganEx, is a bit more sophisticated. It consists of pumps, sensors, heaters and filters to control the flow and temperature of the blood substitute being pushed through the body. The Yale team's secret formulation is a proprietary liquid of electrolytes, vitamins, amino acids and other nutrients, plus a cocktail of 13 drugs that reduce cell death and cellular stress and regulate the immune and nervous systems.

The researchers mixed the synthetic fluid with pig blood in a series of pumps designed to control its flow and temperature throughout the circulatory system. This special mixture, the researchers hypothesized, helped rejuvenate the pig's organs.

It is still unknown whether the pig organs revived by the Yale researchers would begin to function normally on their own if transplanted into another recipient. The next step should be to transplant the organs into other pigs to see how well they work compared to organs preserved in the conventional way.

In their study, the authors speculate that the system may also lead to new treatments for people who have suffered a heart attack if it is able to restore normal heart function in a living patient. The idea is still far from human essay, but if it is possible, experts say, it raises some interesting ethical choices.