An article published in Medium earlier this week brought a never-ending debate back to the fore.

It was written as an independent research project by an author whose nickname is nusenu.

The title:

How Malicious Tor Relays are Exploiting Users in 2020 (Part I)

The controversial article states that if you visit a website using Tor, in the hope that you remain anonymous and stay away from any unwanted monitoring, censorship or even a simple web tracking for marketing purposes…

Μία Then one in four of these visits (maybe more!) Will be deliberately monitored by cybercriminals.

This sounds very disturbing, as it seems that the use of Tor. makes you less secure than you already are. So getting back to a normal browser can be an important step.

So let's take a quick look at how Tor works, how fraudsters (and countries with strict censorship and surveillance rules) can abuse the network. Is the above title really valid?

The Tor Network (Tor is the abbreviation of the onion router). The onion is used in the name as it has many layers. The network was originally designed by US Navy, and aims to:

- Hide your actual network location while browsing so that the servers do not know where you are.

- Making it harder for someone to "join the dots" by detecting web browsing requests coming from your computer.

Based on the above you may think that "this is exactly what a VPN does and not just for my browsing, but for what I do on the internet."

But it is not so.

A VPN (VPN) encrypts all of your network traffic and transmits it in encrypted form to a server VPN running from your VPN provider. This server is connected and accesses the Internet for you to access the internet.

Therefore, any responses to requests made online may be received by your VPN provider and delivered to you in encrypted form.

The encrypted connection between your computer and the VPN is called a VPN tunnel and is theoretically invisible or at least inaccessible to other people on the Internet.

So we can say that a VPN deals with the first issue mentioned above: It obscures your actual location on the network.

But VPN does not deal with the second issue, which is to make it difficult for someone to "join the dots".

Sure, with a VPN it is difficult for most people to join the dots, but it does not prevent anyone from doing so, for the simple reason that the VPN provider always knows where your requests are coming from, where they are going and what data you are sending and what you receive.

So the VPN provider becomes essentially your new ISP, and has the same degree of visibility in your online life as a regular ISP.

Why not use two VPNs?

Now you are probably thinking: “Why not use two VPNs in a row? In technical terms, why not create a VPN tunnel inside a VPN tunnel?

You will encrypt your network traffic to be decrypted by VPN2, and then you will encrypt it again for VPN1 to decrypt it and send it to VPN1.

This way, VPN1 will know where your traffic came from and VPN2 will know where it is going. A condition of course in this is that two providers do not work together because if at some point the dots work together they can be joined again.

Why stop at two?

As you can see, even if you use two VPNs, you are not completely secure. Why;

First, by using two identical VPNs at a time, there is an obvious pattern in your connections, and therefore a consequence in the path that a researcher (or scammer) could take to try to locate you.

Your traffic may take a much more complicated route, but it takes the same route every time. So it may be worth the time and effort of a criminal (or authorities) to work backwards on both levels of VPNs, even if it means double the amount of work, or double the number of warrants.

Second, there is always the possibility that the two VPN providers you choose are owned or operated by the same company.

In other words, the technical, physical and legal separation between the two VPNs may not be as serious as one might expect. Especially if there are warrants.

So why not use three VPNs, with one in the middle that knows neither who you are nor where you are going?

And why not change these VPNs on a regular basis to add even more mystery to the equation?

Well, that's what Tor is Project.

A team computers, offered by volunteers around the world, act as anonymous relays to provide a virtually randomized and layered VPN to people browsing the Tor network.

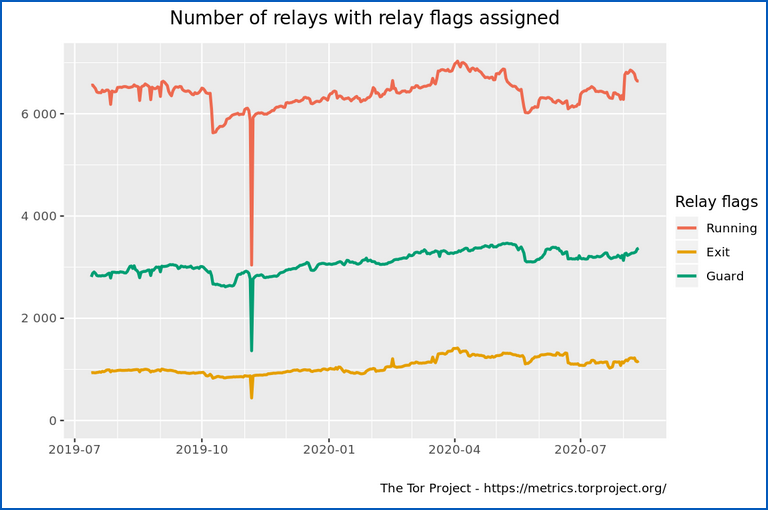

Last year, the total number of relays (computers) available on the Tor network was between 6000 and 7000. Each Tor circuit is configured to use three random relays to form a VPN of three tunnels.

Your computer chooses which relay to use, not the network itself, so there are indeed many constantly changing situations and a lot of mystery in bouncing your motion through the Tor network and back.

Your computer gets the public encryption keys for each of the relays from the circuit that controls them, and then encrypts the data you send using three levels of onion-like encryption so that the current relay can remove only the outer layer of encryption before handing the data over to the next.

Let's see how:

- Relay 1 knows who you are, but not where you are going or what you want to say.

- Relay 3 knows where you are going but not who you are.

- Relay 2 has the other two relays without knowing who you are or where you are going, making it much harder for relays 1 and 3 to meet, even if they intend to do so.

It is not so accidental

In the diagram above, you will notice that the green line in the middle indicates the special Tor relays also known as protective or full input protection relays, which are the subset of the working relays considered suitable for the first hop in a 3-relay circuit. .

(For technical reasons, the Tor network actually uses the same input protector for all your connections for about two months at a time, which reduces randomness on Tor circuits. But we won't go into that detail.)

Similarly, the orange line at the bottom indicates the outputs or output nodes, which are relays that are considered reliable enough for the last hop in a circuit.

Note that only around 1000 output nodes are active here at any one time, out of the 6000 to 7000 available in total.

Where is the problem;

Although Tor output nodes cannot tell you where you are, they see the final, decrypted motion and its ultimate destination because it is the output node that removes the final layer of Tor encryption.

In other words, if you use Tor to browse a non-HTTPS (non-encrypted) webpage, then the Tor output node that manages your traffic can not only monitor and modify your outgoing requests, but also harm them. any returning answers.

And with only 1000 output nodes available on average, a scammer who wants to gain control of a significant percentage of costs does not need to configure thousands or tens of thousands of servers. A few hundred will do the job.

And this type of interference is what Nusenu claims to have detected in the Tor network on a scale that can sometimes include up to a quarter of the available output nodes.

More specifically, Nusenu claims that, during 2020, hundreds of Tor relays in the list of "output nodes" were created by malicious volunteers with less clear motives:

Ένα από τα κίνητρα φαίνεται να είναι απλό: το κέρδος. Πραγματοποιούν προσωπικές επιθέσεις εναντίον χρηστών Tor χειραγωγώντας την κυκλοφορία καθώς ρέει μέσω των ρελέ εξόδου. Φαίνεται ότι συμβαίνει συνήθως σε ιστότοπους που σχετίζονται με κρυπτονομίσματα, δηλαδή υπηρεσίες bitcoin. Αντικατέστησαν τις διευθύνσεις bitcoin στην κίνηση HTTP για να ανακατευθύνουν τις συναλλαγές στα πορτοφόλια τους αντί για τη διεύθυνση bitcoin που παρείχε ο user.

Simply put, Nusenu claims that these scammers are waiting in the corner for cryptocurrency users.

HTTP is harmful

Many times you may not type https: // when you type URLs into your browser, but you still end up with a site that uses HTTPS.

Often, the server you want to visit responds to an HTTP request with a response that tells the browser: "From now on, do not use the old HTTP" and your browser will remember it and automatically upgrade all future connections. on this site in HTTPS.

These "From now on, do not use the old HTTP" is also known as HSTS, an abbreviation of HTTP Strict Transport Security, and is supposed to keep you safe from any traffic monitoring and manipulation.

But there is a problem: if scammers steal your first non-HTTPS connection to a site you really should only access via HTTPS they can:

They keep you on HTTP at the trapped output node while you think you are on HTTPS.

Rewrite any responses from the final destination to replace any HTTPS links with HTTP. This prevents your browser from upgrading to HTTPS, thus keeping it stuck in plain old HTTP.

What to do?

Here are some tips:

- Do not forget to enter https: // at the beginning of each URL!

- If you are a webmaster, be sure to use HSTS to tell your visitors not to use HTTP next time.

- If you are the administrator of a site where privacy and security are not negotiable, consider adding your site to the HSTS preload list. It's a list of sites that all major browsers will always use HTTPS, no matter what the URL says.

- If your browser supports it, consider turning off HTTP completely. For example, Firefox now has a non-default configuration feature (flag) called dom.security.https_only_mode. Some older sites may not work properly with this setting enabled, but if you want security, give it a try!